By HENRY FREDERICK / Headline Surfer

By HENRY FREDERICK / Headline SurferDAYTONA BEACH, Fla. -- Let's face it: Anything in life worth pursuing takes everything we've got.

Sometimes at our own peril.

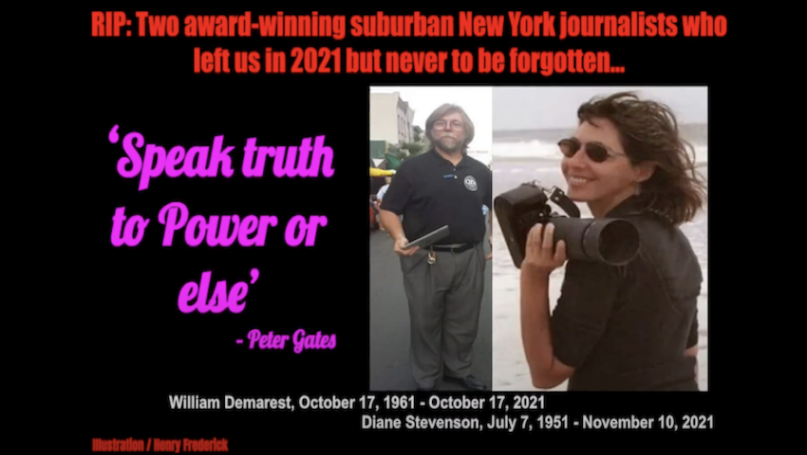

In the latter part of 2021, I lost two journalism colleagues who were clearly a part of my daily training: Bill Demarest, was only 60 and of all the days to die, it had to be on his 60th birthday. The second to die was Diane Stevenson, who was 70.

The ever-changing dynamics in print newspapers didn't value them and many others who were far better than what's out there today in press release journalism with a cheap headline. Both won several prestigious awards, including the New York Associated Press.

How or why they died is not as important here as to who and what they were in the years when they lived their lives - in journalism careers they loved and balancing it all out with raising families.

Demarest was a big guy, who was low-key in his demeanor, but not won to back down from saying what needed to be said.

Stevenson was the lone woman among a photo staff of four, but she answered to no one. Not because she couldn't take direction or pursue an assignment, To the contrary, she knew what had to be done and just did it.

"You've got those negatives?" a metro editor barked in her direction at any one of the four. Stevenson without lifting her head snapped back, "Look in your folders.!"

A photojournalist in a metro newsroom in the late '80s and early '90s was a rarity. Diane Stevenson was tough as nails with a killer smile - not with any sexist hints implied or otherwise, just the reality of a gal who never allowed anyone or anything to wipe that smile off her face - like Michael Jordan with that wagging tongue flying through the air for a monster dunk.

Stevenson was always on the go except when she was unloading pics from her camera and into a processing machine. Otherwise, she was out - and because of that, she always got her shot. Her passions were wine and the beach.

Demarest was not a finesse guy. He was all about getting the story with enough details that it could carry a slot on the front page or local front. He was a great deadline writer as well.

Demarest was not a finesse guy. He was all about getting the story with enough details that it could carry a slot on the front page or local front. He was a great deadline writer as well.

His passion was being Daddy to his firstborn, Sam, and umpiring youth baseball games.

Demarest was the third option on the metro desk for hyperlocal news of impact. There was a 1-2 punch on the Sunday front page of Steve Lieberman and Greg Clary. Lieberman was the investigative guy with great sources. Clary was the ultra-skilled finesse writer. While Lieberman-Clary had the Sunday front page, Demarest was counted on for the Monday front, actually far tougher because his story had to be filed by Thursday for the advance weekend production.

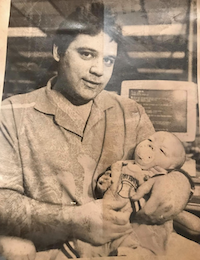

Me, I was the wide-eyed kid from rural northeastern Connecticut whose journalism career consisted of a year at a small weekly, The since defunct Putnam Observer-Patriot, and two years at a small daily, The Willimantic Chronicle, covering city cops and district courts (mostly violent felony cases).

Back in those days, for a kid like me - 27 and raw - getting out there and getting the key elements was not the weakness as much as how to assemble it. In my previous jobs, I was the star reporter with the front-page story and if was crime-related, the adage, if it bleeds it leads, was the way it played out.

My son, "Little Henry" was born in Nyack Hospital in 1993, and was 3 when we left for Daytona. He's now 28.

My son, "Little Henry" was born in Nyack Hospital in 1993, and was 3 when we left for Daytona. He's now 28.

I remember the first time driving over from Storrs, Conn., where I lived at the time, for the job interview (was recommended to the newspaper by a recruiter) and crossing the Tappan Zee Bridge in New York on I-287 and into Rockland County. It was like I was in another world.

But here in this new world, while psyched that I was hired to work for a metro daily newspaper, I was lost. Enter, Bill Demarest. He'd make an outline with these questions: What's your lead? What's the main point of the story? What's the strongest quote? What about secondary facts and voices?

Stevenson, too, would contribute to my understanding of a given assignment. " Hey, Hank, why am I shooting this image at this angle? I'm giving your lead the visual to carry the story on the page."

It started to come together for me, slowly, but surely. Then, with a new editor coming in, by the name of Caesar Andrews, and shaking things up, he called me in and asked me flat out. "What's your dream beat?"

"I don't have the experience and I have to wait my time," I replied. He asked me again, this time with sternness in his voice. "Mr. Frederick! Henry, what is the beat you really want?"

"I looked at him with my poker face on, "Cops and courts, sir."

He responded, "Yeah, I figured as much from the bylines you've generated - you've seized every opportunity."

So who has helped you with your writing, Henry? You've seemed to make some great adjustments."

"Bill Demarest, consistent reinforcement of the story elements. And the photographer?"

"Diane Stevenson, with that killer smile and determined to get that visual. Something I learned could be achieved through words, too."

What the new editor didn't tell me, but Demarest confided to me later impressed Andrews was a story I had written on deadline on a brutal gas station murder. Lieberman was brought in to flush out a few details and the entire front page was torn apart for that story.

The story was an honorable mention for "spot news" among large newspapers from the New York Associated Press Journalism Awards Competition.

I spent seven years in Rockland and wasn't the easiest guy to get along with. I was just always so focused on getting that big cops & courts crime story every day, whatever it was, and getting my byline either on the front page for the next morning and perhaps a more in-depth follow-up spread for the Sunday or Monday papers under Clary/Lieberman or Demarest.

When I left New York for my chance to build on the more demanding cops & courts beat in Daytona and a chance to be a part of the Daytona 500, I had that one award-winning byline - good enough to get me in the door.

When I left New York for my chance to build on the more demanding cops & courts beat in Daytona and a chance to be a part of the Daytona 500, I had that one award-winning byline - good enough to get me in the door.

I left West Nyack, NY, the newspaper's location, back in July 1996, and that was the last I ever saw of Demarest and Stevenson in person, though thanks to social media, we kept in touch through the years.

Today, I have 115 award-winning byline stories (but who's counting, right?) - more than whole scores of newsrooms. I owe a lot of that to Bill Demarest and Diane Stevenson.

I made the video to go with this write-up two weeks ago, but I just couldn't write about what they and so many others from back in the day have meant so much to me, but it was all really right there in the Ringo Starr song, "It Don't Come Easy."

I never gave up on me and neither did they when it could have been just as easy to invest in someone else, not as strong-willed and difficult to deal with personality-wise. Then the lyrics to the song hit me:

Got to pay your dues if you wanna sing the blues, And you know it doesn't come easy.

You don't have to shout or leap about, You can even play them easy.

Thank you, Bill and Diane. Rest easy for you both taught me well and I love and admire you both for it.

Multimedia Video:

About the Byline Writer: Henry Frederick is a member of the working press and publisher of Headline Surfer, the award-winning 24/7 internet news outlet launched in 2008 along the I-4 tourism corridor in greater Daytona Beach to Orlando from Lake Mary, Florida via HeadlineSurfer.com. Frederick has amassed 115 award-winning bylines in print & online. He earned his Master of Arts in New Media Journalism from Full Sail University in 2019. He was a breaking news reporter (metro cops & courts beat) for the Daytona Beach News-Journal for nearly a decade. And Before that worked the same beat for The Journal-News/Gannett Suburban Newspapers in Rockland/Westchester counties, NY, dating back to 1989. Having witnessed the execution of serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Florida's death chamber and covering other high-profile cases such as the George Zimmerman murder trial, Frederick has appeared on national crime shows on Discovery ID, Reelz, and the Oxygen Network series "Snapped" for his analysis. AWJ:

About the Byline Writer: Henry Frederick is a member of the working press and publisher of Headline Surfer, the award-winning 24/7 internet news outlet launched in 2008 along the I-4 tourism corridor in greater Daytona Beach to Orlando from Lake Mary, Florida via HeadlineSurfer.com. Frederick has amassed 115 award-winning bylines in print & online. He earned his Master of Arts in New Media Journalism from Full Sail University in 2019. He was a breaking news reporter (metro cops & courts beat) for the Daytona Beach News-Journal for nearly a decade. And Before that worked the same beat for The Journal-News/Gannett Suburban Newspapers in Rockland/Westchester counties, NY, dating back to 1989. Having witnessed the execution of serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Florida's death chamber and covering other high-profile cases such as the George Zimmerman murder trial, Frederick has appeared on national crime shows on Discovery ID, Reelz, and the Oxygen Network series "Snapped" for his analysis. AWJ: